Companion

Companion![]() The

The  Companion

Companion

Home ¦ Index ¦ FAQ ¦ Encyclopaedia ¦ Timeline ¦ Songs ¦ Gallery ¦ E-mail

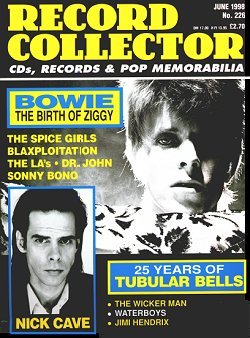

by Mark Paytress - Record Collector (June 1998)

At the start of 1972, David Bowie was still struggling to shake off the one-hit wonder tag which had haunted him since "Space Oddity" in 1969. By the end of it, he was rock's most controversial figure. His ingenuous "I'm gay!" claim to Melody Maker, back in January, was an awesome first strike.

The memorably titled "The Rise And The Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars", released that summer, more than justified the media's gaze. By December, it was scooping up 'Album Of The Year' plaudits. Better still, for every Bowie convert, there were at least two who'd accuse him of destroying the very foundations on which rock'n'roll, nay rock, was based. He was pantomime, they said, a charlatan who was undermining an honest art form with a series of tacky costume changes.

His detractors also dismissed his music as a backwards step: rehashed rock'n'roll riffs made trashier via Bowie's favourite musical looking-glass, the Velvet Underground, was not, they said, a natural progression from the delicate artistry of singer-songwriters and symphonic rockers. And the hype. Oh the hype!

Ever since the Beatles started having hits with their own songs, pop had been growing up. Fast. Perhaps to fast. Ten years after "Love Me Do", records were being described in language stolen from classical music critics or literature lectures. Rock stars were being feted as Picassos with guitars. They stroked their beards, while rock magazines stroked their egos. David Bowie's "Ziggy Stardust" - the album, the character, the stage-show, the (aborted) movie - implanted a seed that was to destroy a large part of all that. Punk rock would have looked (and probably sounded) quite different had Bowie not messed up the rules five years (oh, spooky) earlier. The man had brains. He never subscribed to the notion of being a musical revolutionary destined to remain unheard outside his own cabalistic circle. Instead, Bowie calculated. He did so because "Ziggy Stardust" was, after all, a concept album with its own narrative thrust, and Bowie a star who quickly became so big that journalists were kept at bay. A perfect Mod face in the 60s obsessed with buttons and stitching, the Clockwork Orange-era Bowie had tailored rock'n'roll's regulations to suit himself. He was a star and an anti-star whose tangle of contradictions epitomised both depth and its flightiness.

ZIGGY STARDUST: THE COUNTDOWN

10... Suburbia

The peace of the Jones family's post-war dream-home in Bromley, Kent, is shattered one day in 1956. That's when David Bowie discovers the potency of rock'n'roll while watching his cousin Kristina dance to Elvis Presley's "Hound Dog". He immerses himself in the sounds of (mainly) black America, flirts with skiffle at a scout camp, and gets himself a saxophone. By 1963, he's honking away on stage (and singing) with the Konrads. Within a year, he's off to join the grittier R&B movement, and releases the first of several singles with a variety of backing bands. They all flop. In 1967, now restyled David Bowie, he flees the suburbs and heads for the city, chaperoned by an old-school manager, Kenneth Pitt.

9... Terry

Alias David Bowie, the 1985 biography by Peter and Leni Gillman, added a hitherto unexplored dimension to the roots of Bowie's work - his family. When Bowie's office rejected any relationship between his work and "the trauma that have afflicted his family", it was as believable as a Home Secretary insisting there was no connection between poverty and crime. Terry Burns, Bowie's half-brother, was, by all accounts, the outsider in the family. He was also a schizophrenic who, by the mid-60s. was living in his own personal hell. Intelligent, older and free-thinking, Terry - who was rarely at home - was an object of hero-worship for Bowie. It was easy to confuse this literate jazz-buff with genius. Indeed, the relationship between madness and art has been a hot potato among the chattering classes down the centuries, and young David, sensing the stiffing ordinariness of the world was not for him, found solace in his half-brother. Terry, who became an inspiration for several Bowie songs, spent much time in institutions until his suicide in 1985.

8...Vince

The Rise and Fall of rock'n'roll hangover Vince Taylor is still a little-known tale outside rock's minutiae-seekers. But Bowie, who enjoyed a memorable encounter with the "Brand New Cadillac" man in 1966, knew all about it. He once met Taylor who was on all fours outside Tottenham Court tube station ranting about the world's innermost secrets. "I thought, there's something in this," he said later. "This is just too good!"

No one quite knows what unhooked Vince Taylor's mind, though drugs and drink did form part of his daily diet. Before spouting mysticism and declaring himself to be Jesus, which he was wont do by 1967, Vince Taylor was a leather-clad rocker who'd been an Elvis-like hero to French audiences earlier in the decade. A Jekyll and Hyde character, Taylor's behaviour had grown increasingly erratic by 1965. Two years later, a bizarre tour ended abruptly when he sacked his band on stage and was almost lynched by his audience. (Gratuitous comparison with the Fall's Mark E. Smith here). Bowie has more recently acknowledged Vince Taylor as an inspiration for his Ziggy Stardust character. "He always stayed in my mind as an example of what can happen in rock'n'roll," he told Paul Du Noyer. As, no doubt, did the fates of later Bowie Heroes, Syd Barrett and Peter Green...

7...Art

Through Kenneth Pitt's guidance and patronage, Bowie began to glimpse the finer things in life. Entertainment was no longer a distraction from mundanity but an energetic vehicle for ideas. Encouraged by his manager, David sought to become a different kind of pop star for more 'sophisticated', artful times. The result? His first album, issued on Decca's 'progressive pop' Deram imprint, struggled to sell into three-figures. Undeterred, Bowie buried himself in classic literature, studied mime with Lindsay Kemp. appeared in a couple of low-budget films, and wrote his first rock opera, "Ernie Johnson". When the bills began to pile up, he formed an arty cabaret trio, Feathers, and converted a back-room in a Beckenham pub into an Arts Lab.

6...Success

Early in 1969, the dilettante returned to songwriting with "Space Oddity". Everyone who heard it was bowled over, except for producer Tony Visconti, who believed Bowie would be wasted in the commercial market and refused to have anything to do with it.

With a new, one-year deal with Philips/Mercury, Bowie confidently fed the single all the right ingredients. In the aftermath of the moon landing, the slow-moving 45 landed in the U.K. charts in the autumn, stalling at No. 5. Bowie's spaceship came hurtling back with a bump, though, when he toured the country with Humble Pie. When he tried his mime act out on hard-rock audience, the young star was forced to beat a phlegm-covered retreat.

5...Angie

Ziggy Stardust never thought he'd need so many people, but by 1970, Bowie certainly did. The first of his triumvirate of helpers was a loud American business studies student named Angela Barnett. They'd met in April 1969, moved to Beckenham (the grandiosely titled Haddon Hall) later that year, and had married by March 1970. Having Angie around to provide love and encouragement meant there was little room for Ken Pitt to manoeuvre. By spring 1970, he was gone, banished in away that was out of keeping with his gentlemanly ways. With Angie there to do the hustling, Bowie allowed himself to drop the guise of formality which he'd maintained in Pitt's presence. Now, he was free to make a more wholehearted assault on the rock business that had been ignoring him for so long.

4...Ronno

"My Jeff Beck", said Bowie years later. Mick Ronson was a vital ingredient in the singer's transition from an acoustic-touting artsy bard into a fully-fledged rock'n'roller. Having perfected his guitar skills in Hull's finest beat combo, the Rats, Mick Ronson first teamed up with Bowie in February 1970, at a time when the singer was toying with the idea of returning to a band format. With Tony Visconti (bass) and John Cambridge (drums), the pair hit it off as the Hype, a proto-Glam unit fond of dressing up and rocking out. That project was short-lived, and after Ronson and Visconti created a heavy-metal bedrock for Bowie's songs on "The Man Who Sold The World" album, the shy guitarist returned to Hull until he got a second call from Bowie in April 1971.

3...Tony Defries

Alias the Man Who Sold Bowie to the World. Tony Defries entered Bowie's life in March 1970, quickly won his trust, and oversaw the transformation in his career that rescued him from being a fad-chasing joke to the Man of the Seventies. Defries created the conditions in which Bowie was able to flourish. He secured a favourable deal with RCA, gave Bowie time and space in which to write, and cocooned him in all the trappings of stardom - huge bouncers, top-whack hotels, glitzy hangers-on, exclusivity - even before the sales figures came in. He planned Bowie's campaign with military precision, flying writers in from the States to see warm-up dates, cultivating the support of the U.K. music weeklies, and talking up his charge at every opportunity.

2...Warhol

Bowie first heard the Velvet Underground late in 1966, when Ken Pitt returned from a visit to New York with a test pressing of the band's debut album. The record ran the gamut from pop romanticism to debauchery and destruction, a perfect mirror to the group's name. More than that: the Velvet Underground were like the Monkees in reverse - brought into existence through the patronage of artist Andy Warhol, they were puppets of a more sinister kind, wiping smiles from well-fed faces with mixed-media shows that extended the pleasure principle to incorporate pain. Another Bowie icon, Iggy Pop, did much the same thing, only with more drama, and if Bowie aspired to anything during the early months of the 70's, then it was to have the body of Iggy with the mind of Andy Warhol. Like Warhol, Bowie relished the contemporary themes of celebrity and disaster, which would climax so spectacularly in the Ziggy Stardust project. He also took on board the artist's idea of star 'construction', which ran counter to the classical view of 'an artist'. In Warhol's world, not only art but the artist himself was artifice. For someone with a delicate ego like David Bowie, that was one hell of a protection.

1...Bolan

Marc Bolan had been an old adversary of Bowie's since the mid-60s, when both could be found in noted central London rock hangouts getting high on the whiff of celebrity. By 1971, Bolan was being hailed as the first Superstar of the new decade. Although he'd landed on the pop charts from an impeccable hippie background, Bolan was quickly perceived as a new kind of performer, someone who brought the glamour, the simplicity and the sex back into pop. His T.Rex sound harked back to the three-chord trick of vintage rock'n'roll, while his image was in stark contrast to the blue-jean rock that had cast a dull shadow over the legacy of psychedelia. What David Bowie brought to the early 70s was all this - and more. Unlike Bolan, who found change difficult when maintaining his long-fought for stardom was at stake, Bowie - as the song goes - made the concept of change the theme of his life. In that respect, he could earn at least some respect from the otherwise mistrustful progressive quarters. Which is why, unlike Bolan, Bowie sold albums and eventually broke in America, too. Bolan enjoyed his stardom; Bowie (or was it Ziggy?!) critiqued his.

... Blast off!

"The Rise and Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars" was released in June 1972. Its highest chart placing was No. 5 in the U.K.. It failed to chart in the U.S.. In last year's Channel 4/HMV/The Guardian "Music of the Millennium' poll, it came in at No. 20.

---This page last modified: 13 Dec 2018---