Companion

Companion![]() The

The  Companion

Companion

Home ¦ Index ¦ FAQ ¦ Encyclopaedia ¦ Timeline ¦ Songs ¦ Gallery ¦ E-mail

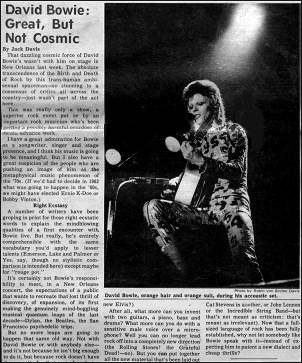

David Bowie, orange hair and orange

suit, during his acoustic set.

(Photo by Robin von Breton Davis)

Jack Davis - New Orleans Figaro (2 December 1972)

That dazzling cosmic force of David Bowie's wasn't with him on stage in New Orleans last week. The absolute transcendence of the Birth and Death of Rock by this trans-human ambisexual spaceman - so stunning to a consensus of critics all across the country - just wasn't part of the act here.

This was really only a show, a superior rock event put on by an important rock musician who's been getting a possibly harmful overdose of media advance work.

I have great admiration for Bowie as a songwriter, singer and stage presence, and I think his music is going to be meaningful. But I also have a great suspicion of the people who are pushing an image of him as the metaphysical music phenomenon of the 70's (If we had to decide in 1962 what was going to happen in the 60's we might have elected Ernie K-Doe or Bobby Vinton.)

Right Ecstasy

A number of writers have been groping in print for the right ecstatic words to explain the mind-blowing qualities of a first encounter with Bowie live. But really, he's entirely comprehensible, with the same vocabulary you'd apply to lesser talents (Emerson, Lake and Palmer or Yes, say, though no stylistic comparison is intended here) except maybe for "rouge pot."Its certainly not Bowie's responsibility to meet, in a New Orleans concert, the expectations of a public that wants to recreate that lost thrill of discovery, of expansion, of its first making the genuinely quantum leaps of the last decade - Dylan, the Beatles, the San Francisco psychedelic trips.

But no more leaps are going to happen that same old way. Not with David Bowie or with anybody else - and its not because he isn't big enough to do it, but because rock doesn't have the capacity for that explosion any more (Remember all the press flap about James Taylor movement, or Elton John - and how, ultimately, nobody ever became the new Elvis?)

After all, what more can you invent with two guitars, a piano, bass and drums? What more can you do with a sensitive male voice over a microphone? Well you can no longer lead rock off into a completely new direction (the Rolling Stones! the Grateful Dead! -no). But you can put together all the new material that's been laid out there, but not quite consolidated, over the past decade.

To pretend that a performer is opening new musical territory is misleading - and that's what people are imagining of David Bowie now. It's also unfair to dismiss "derivative" as automatically bad, especially in Bowie's eclectic case (yes, he sounds like the Bee Gees in a place or two, or Cat Stevens in another, or John Lennon or the Incredible String Band - but that's not meant as criticism; that's meant as irrelevant). Now that's a full sized language of rock that's been fully established, why not let somebody like Bowie speak with it - instead of expecting him to patent a new dialect and cheap thrills?

While last Wednesday's concert was not the electrifying new world that many had been expecting, it was still the most pleasant rock concert in New Orleans in months. Bowie gives a good, varied and conscientious performance at a time when most rock concert organisers and musicians are late, sloppy and callous toward their audiences.

His people seemed to have control of the Warehouse. Signs warned that photographers were not allowed (merely a superstar promotion gimmick, I was told by a record man). Warehouse owners and staff were banned from the stage, and a pair of body guards said to be karate black belts, made sure that nobody violated security (by coming within five feet of the stage.) And, miraculously, all of the people sitting on the floor in front of the stage actually stayed seated, which must be some kind of a first.

Bowie's Warehouse

It seemed to be David Bowie's building even more than it had seemed to be Leon Russell's when Leon moved in with a big band and film and recording crews for two nights.And there was no other act on the bill - unless you count local folksinger Les Moore, but he's like one of the crowd. White Witch, an Alice Cooper imitation, hadn't been able to get out of Florida. That seemed a lucky break, when Wet Willie, that good little boogie band from Mobile and Macon, was booked to fill the hole (thus promising good raunchy dance music, in place of hokey decadence). But they missed the plane.

So Les Moore's versions of Arlo Guthrie and Donovan were left to set the mood for Bowie's strobes (who else uses strobes these days, besides James Brown?); the make-up and jump-suits; the shag-cut, crew cut, black-haired, white side-burned bassman; and Walter Carlos's synthesized fourth movement of Ludwig Van's Clockwork Ninth.

Spry and Bouncing

Bowie flashes out spry and bouncing in an orange playsuit with one digit numbers all over it. He's benign, personable, friendly and direct - a genuinely likeable being, not the hard-edged drag terror from Mars.(This raises one unfortunately reversed conception about who Bowie's Ziggy Stardust is, in relation to the world of "A Clockwork Orange" - the most fascicle of the associations now making the rounds. Ziggy isn't an ultra-violent Alex. He's exactly the opposite: A humane romantic, looking for glints of love in an increasingly passionless world. If he's anything from the film, he's Kubrick, hating and knowing the coldness.)

With black leather jacket, left, and without it during his encore,

Bowie's black pants were the world's tightest. (Photo by Robin von Breton Davis)Fretting all the time over the techicnal quality of his sound, Bowie varies the full hardness of Who rock (his "Hang Onto Yourself," for an opener) with the delicacy of an acoustic set ("Space Oddity," "Andy Warhol," "Drive-Ins"), then dodges back to the dressing room. The Spiders from Mars, driven by Mick Ronson's fine guitar work and dressed like futuristic Restoration fops (knee britches, buckle shoes), carry into a long jam on "The Width of A Circle." The Bowie's back for "Suffragette City" in a black leather, fur-collared jacket. And at encore time ("Moonage Daydream" & "Rock n Roll Suicide"), he and Ronson return shirtless.

The whole show is done on the full length and breadth of the intensely bright stage - with Bowie and Ronson circling around each other, and virtually galloping at times from the drum set forward to the mike stands for choruses.

In other cities, Bowie did more songs (and, apparently, with a good deal more energy) - like Jacques Brel's "My Death" The Velvet Underground's "Waiting For my Man" and "White Light," and his own "John, I'm Only Dancing."

A critic in Boston went away from the Bowie show "haunted, captivated, not just by its eccentricity, but, I am sure, by its inevitable rightness, far though I am from any conscious recognition of that."

I went away from the Bowie concert curiously satisfied, and sleepy. Were we missing something perhaps? At any rate, I think there's a lot more of David Bowie to come.

---This page last modified: 13 Dec 2018---